Posted Tuesday, August 9 2011 at 00:00

http://www.businessdailyafrica.com/Will+long+arms+of+justice+catch+up+with+system++Okemo++Gichuru/-/539546/1215714/-/item/2/-/pwxgvhz/-/index.html

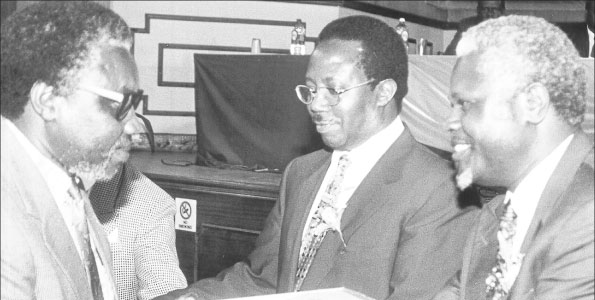

Nambale MP Chris Okemo (right) and Mr Gichuru at a function in 1998. File

If Nambale MP Chris Okemo and former Kenya Power managing director Samuel Gichuru are in the dock (and perhaps rightly so) what happens to Sameer Group or the directors of Vivendi who in the story of Alcatel contracting appear to be complicit in facilitating and channelling the bribes and may even have benefited financially? What about HSBC and Deutsche Bank who received, funnelled and cleaned the illicit money?.

How about the banks in Jersey and Guernsey who harboured the corrupt money, benefited from client fees and provided the legal web of secrecy upon which the entire story is based?

It is on record that the Kenyan politicians are accused of abusing power not only in their demand and alleged receipt of bribes but also through their influence on Parliament to pass laws that are friendly to secrecy and money laundering, by for example, removing clauses that required financial institutions to name individual beneficiaries of firms transacting business with them rather than hiding behind nominee accounts.

Mr Okemo and Mr Gichuru could not have succeeded in moving the alleged corruptly acquired loot to Jersey but for the welcoming conditions provided by Jersey. That Jersey is seeking to prosecute its clients who merely utilised the services they provide is rich irony! Who is prosecuting the British Crown Dependent territory of Jersey?

They probably could not have moved the money without the participation of the banks. In Kenya, the British, in spite of their zeal to go after the two have been seen to be reluctant to investigate a local firm and the matter has been in a lull.

Shouldn’t Britain be prosecuting HSBC in the manner that the Americans prosecuted Enron or Worldcom or at least name and shame it as the US General Accounting Office did in the Case of Citi Bank for handling General Auguste Pinochet’s loot?

Truth is, according to Christian Aid, a charitable organisation of the protestant churches of Britain and Ireland, the UK has a poor record of acting effectively to curb or return illicit money brought into its land.

Very little has been heard, in terms of prosecution or repatriation of the estimated $1.3 billion that the late General Abacha (of Nigeria) channelled through the 23 London Banks, including Barclays. Mr Okemo and Mr Gichuru may be greedy and bad, if they are guilty. But the UK will, by no means be the greediest and the worst of them all, let alone the most criminal.

But Jersey is not doing this by choice is it? Jersey is doing the minimum necessary to save its own scalp. It is compelled to action by the US lest it is black-listed for promoting money laundering and by the OECD bilateral information exchange agreement compelling it to provide tax and savings related information to its member countries upon request. We shall explain this bilateral information exchange later.

To demonstrate how the world of dirty money works let’s give some time to the curious case of Mauritius, the African island state embroiled in the Okemo, Gichuru case.

Mauritius is a small Island of not more than 1.3 million people, lying in the Indian Ocean in southern Africa. By most measures, Mauritius is one of Africa’s better governed and successful countries.

It is one of Africa’s most diversified economies, starting off as a sugar plantation literally fed by slave labour. It scores highly in all manner of social wellbeing indicators including education, life expectancy and per capita income where it compares favourably with the best in the developing world.

Its system of social protection compares with any other and as a result, desperate poverty, destitution and hunger are low. Stunningly, like Switzerland, Mauritius has no standing army and yet it is as peaceful as any.

Corruption is perceived by citizens and experts alike to be relatively low across the board and in both public and private sectors. Mauritius banking sector is one of the most sophisticated with most people holding their money held in bank deposits rather than as currency.

However, Mauritius is an African leader in a different type of corruption. It provides the conditions favourable for the laundering of money, wealth and profits. It facilitates not just corruption but massive tax evasion and avoidance. Money laundering is the ‘cleaning’ of illicitly gained money to give it the appearance of originating from a legitimate source. Profit laundering is whereby firms use mechanisms such as transfer pricing, mis-invoicing, licensing and others, to conceal and transfer profits from a high tax paying jurisdiction to one in which taxes are low or non-existent.

How does Mauritius do this? It provides off-shore secrecy services. A secrecy jurisdiction, as defined earlier must satisfy two conditions. First, it designs its financial regulations partly to benefit non residents and puts regulations in place to ensure that the identities of those who use these regulations and are concealed.

Mauritius followed the path of other Islands to make itself attractive to attract global banks and earn fees and other benefits from facilitating the easy incorporation of companies and offering secrecy and low tax services as attraction to non-residents.

It designed its regulations to attract secrecy service providers. These are banks, lawyers, accountants, trust companies and others who make money by helping clients to access the services of the secrecy jurisdiction. Richard Murphy of the Tax Justice Network calls the combined result of secrecy jurisdictions and the secrecy services providers the “secrecy world” .

Mauritius is a vibrant secrecy world. This world promotes money laundering. For money laundering to occur, three steps are needed: First, the entry point where the illicit money enters the legitimate financial system.

Second, a series of opaque layers where money moves through the international financial system across borders, and third, the integration of the illicit money into the legitimate economy once its origins have been effectively concealed.

Let’s take the Mr Okemo and Mr Gichuru case to demonstrate how the regulations in Mauritius facilitated or at least favoured the illicit transfer of corruptly acquired Kenyan money into banks domiciled in its territory. Recall that two payments were made into accounts in Mauritius; one directly to company T into as bank account held in Deustche Bank, Mauritius.

This means that Mauritius permitted company T to hold a bank account without the necessity to reveal who the beneficiaries of company T are.

A second part was paid to an agent company registered in Mauritius and acting for the alleged bribery perpetrators into an account held by a high street British bank, HSBC. This company, as we observed is a “shell” company, a fictional entity more or less existing for no other reason than to facilitate scummy transactions. These types of companies abound in offshore secrecy jurisdictions. Mauritius, like other offshore secrecy jurisdictions provide a place for illicit money to hide and be later cleaned up and integrated into the legitimate financial system

Mauritius found itself also embroiled with tax matters involving another of the companies remotely linked to the web of illicit finance discussed above. The issue involves Vodafone and the Indian Government’s pursuit of them for capital gains taxes.

The story dates back to 2007 and is told by a publication of Christian Aid as follows.

Mauritius and India have a Double Taxation Avoidance agreement. One of the implications of this agreement is that if a company considers itself resident in Mauritius (meaning it pays taxes in Mauritius) and if this company does not have permanent establishment in India, then if such a company owns shares in an Indian company, the sale of these shares will not attract capital gains tax in India.

This allows companies registered as Mauritian companies to avoid paying capital gains taxes of between 10 per cent and 40 per cent in India, which will be payable under Indian law. This means that Indian companies or other companies can register in Mauritius as tax residents simply by paying a small fee and receiving a certificate.

To obtain this certificate, such a company merely needs to ensure that at least two Directors are Mauritian, that they maintain a bank account in Mauritius and appoint an auditor.

Here is where Vodafone comes in. Vodafone acquires (buys up) an Indian telephone company Hutchison Essar Ltd (HEL), which was owned by a Hong Kong based company, Hutchison for $11 billion. Vodafone and Hutchison then incorporates firms in Mauritius and Cayman Island to hold the shares of HEL and to conduct the transaction.

By so doing they both sought to avoid capital gains tax estimated by lawyers to be in the neigbourhood of $2 billion. Vodafone argued that the transaction was between two off-shore entities and was outside India’s jurisdiction, it was by a non-resident, with another non-resident in respect of the transfer of a shares of a company which was also non-resident.

India on the other hand, argued that since the assets were in India the deal was liable to capital gains tax and in any case according to Indian law the buyer had the obligation to deduct and withhold capital gains tax. This story of the exploitation of off-shore tax havens jurisdictions by companies to avoid tax is a microcosm of the bigger picture of illicit flows.

The exploitation of Mauritius’ off-shore status is not only by international companies but crucially by Indian companies and rich individuals who set up shell companies such as the one owned by Sameer Investments, basically to shift money out of India (and this case, Kenya) and to take advantage of the Double Taxation avoidance Act to avoid paying taxes or to clean out dirty money.

These same players then return these monies to India as foreign investors to benefit from tax concessions. This is called “round-tripping”. This is why the tiny palm beach island of Mauritius is the biggest foreign investor in India. It accounts for nearly 50 per cent of all foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows into India.

FDI inflows from Mauritius to India amounted to $20 billion cumulatively between 2000 and 2007. These are Indians, concealing money in Mauritius and taking it back as investors and thus cheating the Indian poor and those who pay their fair share of taxes. Maybe, if we look carefully into the data we might find a significant volume of Mauritian FDI coming into Kenya. Who knows whether some of it isn’t the alleged bribery monies round-tripping.

To fully understand the conditions that facilitate the flow of illicit capital across the world, one must map out in greater detail the role of the key players in the system. Topping the list of the dynamics underpinning the world of dirty money flows are politicians, “bunga bunga” parties and the people.

It comes down to the motivation of people in politics and their ethics. If all you care for is being rich and powerful, even when the people you are supposed to be serving languish in poverty and suffering you will identify with Papi Silvio who, when confronted with a bribery case proclaimed that “If I, in taking care of everyone’s interests, also take care of my own, you can’t talk about a conflict of interest”.

World of illicit capital flows

If all that matters is to manipulate political institutions and law to serve greedy interest, then one could do no better than Papi Silvio. Confronted by a group of “Clean hands” prosecutors determined to nail him for fraud and tax evasion and unearth the hundreds of millions of dollars he stashed away in tax havens and off-shore secrecy jurisdictions, Papi Silvio, responded by putting his legal team in-charge of re-writing the laws.

He backed that up with installation of one of these aides as the head of the Justice Commission, made his own personal tax lawyer the minister of economy and finance.

Three henchmen in legal trouble were made parliamentarians to enjoy immunity from prosecution. Not surprisingly, parliament decriminalised the type of accounting he was accused of using to channel bribes; tax evaders suddenly had amnesty.

Faced with a charge of bribing a judge, Papi Silvio had a new law passed granting immunity from prosecution to Italy’s highest ranking leaders.

There is lot more juice in Vanity Fair’s “Dolce Viagra” story if you are interested – including of course the story of the string of sexy babes.