Posted Monday, September 6 2010 at 22:00

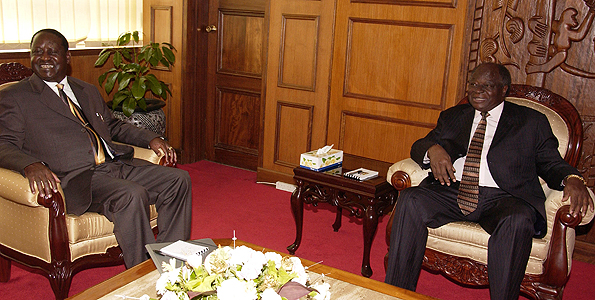

President Mwai Kibaki meets with Prime Minister Raila Odinga at his Harambee house office, Nairobi. PHOTO/ FILE

The long-running saga over the fate of the closed Charterhouse Bank has sucked in President Kibaki and Prime Minister Raila Odinga.

Ongoing hearings of the Parliamentary Committee on Finance heard that American Ambassador Michael Ranneberger wrote to the two principals warning against re-opening of the institution that was shut by the Central Bank of Kenya four years ago.

In the letter dated January 25, 2010, tabled at the hearings, Mr Ranneberger said allowing Charterhouse Bank to re-open “will be a significant setback to the government’s stated commitment to reform.”

He had in an earlier communication to Attorney-General Amos Wako alleged that the bank had been used to launder Sh40 billion, the proceeds he claimed were from the evasion of taxes and related crimes from 1999 to 2006.

The British High Commission made similar allegations in 2006 and 2008, claiming that a member of the committee had “bribed and bullied MPs” on the matter.

Four government institutions that investigated the bank four years ago now seem to be backtracking on their own findings.

The Central Bank, the Kenya Revenue Authority (KRA), the Kenya Anti-Corruption Commission, the office of the Attorney General and the Ministry of Finance are now distancing themselves from the decision to close the bank.

“Given the negative history behind Charterhouse Bank and the Kenyan Government’s declared commitment to real fundamental reform, I strongly encourage you to disapprove any request to permit Charterhouse Bank to resume its business,” wrote Mr Ranneberger.

The letter was copied to Finance minister Uhuru Kenyatta and the Central Bank of Kenya governor, Prof Njuguna Ndung’u.

The Central Bank appointed a statutory manager and shut down the bank in June 2006 following a report by a special investigations team.

The closure was meant to prevent a run on the bank after a leaked report was tabled in Parliament.

“The action was deemed necessary in order to safeguard the interests of depositors, creditors and the institution and is consistent with the provisions of the Banking Act,” said the governor.

After the statutory manager, Ms Rose Detho, took over, the CBK commissioned an audit by PricewaterhouseCoopers, which showed that the management had contravened the Banking Act, the CBK Act and the Central Bank Prudential Regulations.

Based on the August 31, 2006 PwC audit report and observations of the statutory manager, the then Finance minister Amos Kimunya issued a 28-day notice of the intention to cancel the bank’s licence.

But the directors denied any wrongdoing and alleged that the actions against the bank were malicious and discriminatory.

Prof Ndung’u told the committee that the law at the time was inadequate to handle some of the allegations against the bank.

“Most of the allegations against the institution touched on money laundering. The country did not then have a law on money laundering, thus making it difficult for the Central Bank to legally justify any money laundering allegations and take action,” said Prof Ndung’u.

He said the bank was actually in operation, but court orders barred the statutory manager from handling clients.

“It is very sad that after four and a half years, we have not been able to challenge ex-parte orders. You wonder what type of legal system we are running. You cannot challenge ex-parte orders for four years,” he said.

KRA Commissioner-General Michael Waweru said their investigations on tax evasion focused on Charterhouse customers, not the bank itself. Therefore KRA had no hand in the bank’s closure.